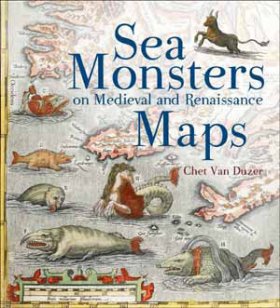

One of the most spectacular and visually fascinating Tet Zoo-related books of recent-ish months is Chet Van Duzer’s Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, published in 2013 by the British Library. I said a few words about this book, and here (at last) is the proper review I’ve been promising. Lavishly illustrated in colour throughout, it has extraordinarily high production values and is a real masterpiece of design; its editorial and print quality is also very high. If you have a serious interest in sea monsters (however you interpret that term), arcane zoology or cryptozoology, the history of seafaring, or in old maps, this book is an essential purchase. It’s also extremely reasonably priced.

One of the most spectacular and visually fascinating Tet Zoo-related books of recent-ish months is Chet Van Duzer’s Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, published in 2013 by the British Library. I said a few words about this book, and here (at last) is the proper review I’ve been promising. Lavishly illustrated in colour throughout, it has extraordinarily high production values and is a real masterpiece of design; its editorial and print quality is also very high. If you have a serious interest in sea monsters (however you interpret that term), arcane zoology or cryptozoology, the history of seafaring, or in old maps, this book is an essential purchase. It’s also extremely reasonably priced.

Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps is not just an atlas of chronologically arranged images; it’s also an analytical study that discusses the trends seen in the maps over time and describes specific maps, their makers, and the creatures they depict. Almost 300 footnotes provide supplementary information. The book is also fully indexed.

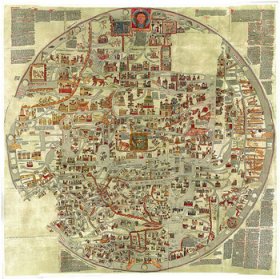

Several themes emerge as you read (or browse) this amazing book. The splendour of the maps themselves is really something to behold. Consider the gigantic maps commissioned by Florentine merchant Baldassare degli Ubriachi in 1400: they were 3.7 m wide and 3.7 m tall and featured “165 figures and animals ... 100 fishes large and small” and much else besides (the maps do not survive). Francesco Becaria (or Beccari), the map-maker concerned, was not paid and we only know about this case because he took legal action against Ubriachi (Van Duzer 2013). The Ebstorf mappamundi – destroyed during WWII – was of similar size at 3.6 m wide and 3.6 m tall.

The Ebstorf mappamundi – destroyed during WWII – was of similar size at 3.6 m wide and 3.6 m tall.

Maps were designed for decoration but also served as documentations of knowledge or as objects of economic or military value; it is clear that many were deliberately designed or commissioned to be attractive or even entertaining, the number and position of the creatures shown upon them mostly being the result of financial and/or aesthetic decision. If you ever thought that the sea monsters shown on old maps were meant to be zoologically meaningful representations of genuine unknown animals, this decorative or entertainment aspect should be ringing proverbial alarm bells. Clearly, the monsters are there to make the maps more interesting. A dislike of empty spaces – Van Duzer (2013) refers to a horror vacui – in part explains why some sea monsters appear where they do, but there are others reasons too.

Olaus Magnus and an economic function for sea monsters

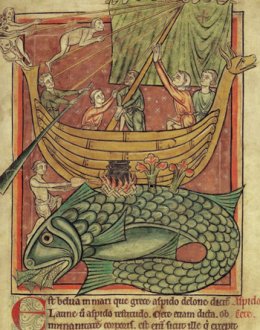

Where did map-makers derive their sea monsters from? While there are cases where artists really did illustrate creatures that they’d heard about or even seen themselves (read on), Van Duzer (2013) explains how the vast majority of monsters were either invented from scratch (this particularly goes for the zany, elaborate monsters that don’t resemble real animals at all), or were copied from other maps or from bestiaries and other books. As might be expected, several works (maps and books) were particularly influential as sources for the illustrations that followed and it is often very easy to demonstrate copying or derivation.

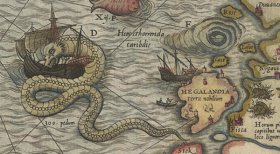

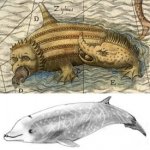

Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina of 1539, printed on nine sheets and surviving as just two copies, is one of the most influential, featuring island-sized ‘whales’, a Nordic sea-serpent, a seal-eating, owl-faced ziphius*, a ‘sea pig’ and various other creatures copied extensively by later map-makers. Those familiar with Loxton & Prothero’s (2013) arguments on the origins of sea-serpent legends will recall the fact that the great marine serpent illustrated by Olaus was derived from earlier drawings and accounts of a land serpent that emerged from a sea cave; Olaus modified this creature for the Carta Marina by severing the link to the land shown in his other illustrations (in his 1555 A Description of the Northern Peoples, he clearly depicted the animal emerging from a cave on the coast).

* The Ziphius of sea-monster lore is a whale-sized creature with a sword-like structure on its back and an owl-like face surrounded by an extensive ruff. It is sometimes portrayed as a spiky quadruped somewhat like a gargantuan hedgehog. I’ve read claims that Ziphius the extant whale (Cuvier’s whale) was the real animal behind Ziphius the sea-monster. Given that the key features of the mythical Ziphius are an owl-like face and an ability to spear animals and ships with the sword on its back, the idea that Ziphius the sea monster has anything to do with Ziphius the whale is fanciful. In any case, Ziphius the whale was named (by Cuvier in 1823) on the basis of a fragmentary fossil skull, not because it was believed linked to Ziphius the sea monster. [Adjacent whale drawing by Bardrock.]

Olaus himself was extensively consulting the Hortus Sanitatis – a giant, richly illustrated encyclopedia published in 1491 – as well as other sources and must have been quite the expert on the sea monsters of the contemporary literature. Was he – as some cryptozoologists might have us believe (Heuvelmans 1968) – an accurate and trustworthy describer of zoological novelties? Well, “Luigi de Anna has suggested that the sea monsters on the map were intended not only to excite the curiosity of the viewer, but also to dissuade fishermen from other countries from entering Scandinavian waters. If this intriguing suggestion is correct, the sea monsters on the map have an innovative economic function” (Van Duzer 2013, p. 86).

Inventing sea monsters and a history of copying

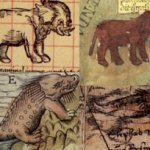

Some creatures on especially old maps illustrate the traditional belief that the creatures of the sea mirrored those of the land. So we have ‘sea dogs’, ‘sea goats’, ‘sea dragons’, ‘sea stags’, ‘sea cows’ (which really are cows, not dugongs or manatees) and even ‘sea chickens’ (yes, really: there’s a marine chicken on the 10th century Gerona Beatus mappamundi). Understandably, some of these creatures are a hodgepodge of dogmatic expectation and of rumours or tales about real animals: an aquatic ‘elephant’ depicted on a 12 century ceiling in Switzerland, for example, might be partly based on walrus sightings, while the ‘sea lions’ of several maps might have been based on otariids but look, as you’ve guessed, like sea-going lions.

Then there are those monsters that seem to be novel inventions. A 1590 manuscript created by Urbano Monte features a gigantic bearded merman with talon-like fingernails; he is shown as being three times taller than an adjacent ship. And what is the story behind Michaelis Tramezini’s flying turtle, first published in 1558 and then copied by several later map-maker? Other creatures have complex backstories and appear, disappear and reappear throughout history: the bizarre murex, the multi-limbed polyp, and the island-like kraken... oh, and: remember, krakens were almost certainly not based on sightings of Architeuthis, the giant squid (Paxton 2004).

RELATED VIDEO

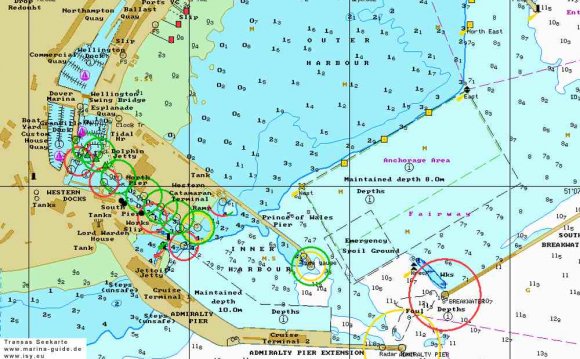

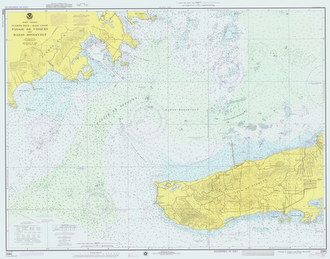

A nautical chart is a graphic representation of a maritime area and adjacent coastal regions. Depending on the scale of the chart, it may show depths of water and heights of land (topographic map), natural features of the seabed, details of the coastline...

A nautical chart is a graphic representation of a maritime area and adjacent coastal regions. Depending on the scale of the chart, it may show depths of water and heights of land (topographic map), natural features of the seabed, details of the coastline...