North Sea oil turned 40 years old this year, outlasting the predictions of doomsayers who claimed that the wells would have run dry years ago.

Since the first oil produced off the north-east coast of Scotland arrived for processing onshore in the summer of 1975, more than 43bn barrels of crude have been pumped. That crude has been worth around £1.4 trillion – a figure greater than the country’s entire national debt – based on an average oil price over the period of $50 per barrel. However, that sum doesn’t come close to reflecting the true value of the North Sea to the British economy.

Total tax receipts from oil and gas production from the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) since 1975 have exceeded £330bn but that figure doesn’t reflect the worth of the industry to the Treasury. The North Sea supports the employment of around 450, 000 people in the UK, all of whom pay income tax and spend their wages on the usual things such as homes and new cars. This is one of the reasons why Aberdeen remains one of the wealthiest enclaves in Britain outside London and the South East.

Extracting the oil from the North Sea has required vast investment and tested the boundaries of British engineering excellence in a way not seen since the industrial revolution. In 1976, the £13bn that was spent to develop the offshore fields was equivalent to 33pc of all UK investment into the manufacturing sector at that time.

Further, offshore drilling using giant platforms capable of sustaining a workforce for months on end in some of the world’s most violent ocean conditions was perfected in the North Sea. The region continues to place the UK at the forefront of the global oil and gas industry and Aberdeen is recognised as a centre of excellence for the kind of advanced subsea technologies which are now being used to open up new oil reserves around the world.

Put simply, the development of the North Sea over the past 40 years represents the best British ingenuity and engineering skill displayed in any sector since the end of the Second World War.

Would the UK have been able to afford a free-to-access National Health Service without the North Sea oil windfall which has arguably helped to fund it?

Although there have been tragedies such as the 1988 Piper Alpha disaster, which killed 167 rig workers, there have been many more triumphs. Not least that the existence of a significant domestic oil and gas industry has helped to sustain the growth of some of the country’s most successful listed companies such as Royal Dutch Shell and BP, two of the biggest companies in the FTSE 100.

And this is why the country cannot afford to give up on its shrinking offshore oil and gas industry, despite the protests of the climate change lobby and economic cranks who dismiss its overall importance to British society. Anyone who believes that the petroleum industries have had their day needs to think again – and that includes some policymakers within Government.

Despite some predictions that oil production in the UKCS should have dried up 15 years ago, there are still thought to be billions of barrels of crude that can be economically extracted at a lower profit.

That is equal to as much as £788bn in revenue and a possible £100bn haul in tax receipts for the Government before the region’s riches are entirely exhausted.

This may be some way below the, but it is hard to see public finances holding up without it, especially with the budget deficit running at £90bn, or 5pc of gross domestic product.

Oil and Gas UK – the trade body responsible for the North Sea – will release its annual economic report on the region next week. This report will provide the first clear snapshot of how the region is coping with falling oil prices.

Instead of preparing for the end of North Sea oil and gas, perhaps the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) should be spending more time thinking about maximising its long-term future. It now has a clear road map set out by Sir Ian in terms of how it can continue to make a significant economic contribution to the UK.

After a slow start, important recommendations of the review have now been adopted – most notably the formation of the Oil and Gas Authority. The OGA has responsibility for the North Sea as the overarching regulator for the petroleum industry both on and offshore across the UK.

However, with the industry having to adapt to the realities of falling world oil prices and the vast cost of decommissioning oil production facilities, the review has arguably come a decade too late to avoid the North Sea slipping into terminal decline.

Although George Osborne, the Chancellor, improved the fiscal terms for investing in the sector in his last Budget, more will have to be done to encourage major oil companies to remain in Aberdeen. Lower oil prices are forcing companies to review their operations around the world and new basins opening up in the Arctic and in Brazil mean that the Government will have to provide more incentives to drillers and stop viewing the North Sea as a convenient cash cow to be milked at every opportunity.

Finally, the significant cost of decommissioning old oil and gas facilities will have to be partly funded by the Government in the form of subsidies. As older North Sea fields begin to run dry over the next 25 years, it is estimated that £40bn will have to be spent removing redundant platforms and pipelines as well as plugging spent oil wells.

Under current rules, oil companies dismantling field infrastructure in the North Sea can reclaim a significant share of their costs in the form of a tax refund. However, the process is complicated and potentially subject to change as governments come and go over the next 25 years.

RELATED VIDEO

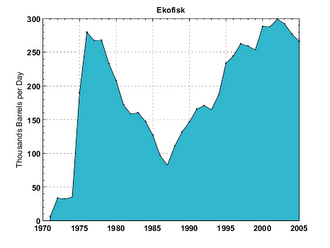

Ekofisk is an oil field in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea about 200 miles (320 km) southwest of Stavanger. Discovered in 1969, it remains one of the most important oil fields in the North Sea. Production began in 1971 after the construction of a series of...

Ekofisk is an oil field in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea about 200 miles (320 km) southwest of Stavanger. Discovered in 1969, it remains one of the most important oil fields in the North Sea. Production began in 1971 after the construction of a series of...