Try to keep it pumping

Try to keep it pumping

WHEN the North Sea oil- and gasfields were booming, inefficiencies mushroomed. Now, times are tough—and it may be too late for belt-tightening. The offshore industry, particularly the British bit of it, is squeezed between a lower oil price, stubbornly high costs, an ageing infrastructure and a looming bill of many billions of dollars for decommissioning old platforms.

The result threatens the profitable and unprofitable alike. If even a few companies which use the pipelines and terminals shut down, then the bill lands all the more heavily—and perhaps cripplingly—on the survivors. Similarly, if a piece of the infrastructure breaks (or its operator goes bust) then everyone who uses it is in trouble.

Operating expenditures in North Sea oil have doubled in 15 years. Only a fifth of that increase, at most, is because of increased activity. The biggest reason is inflated costs, reckon consultants at McKinsey, followed by pure inefficiency, such as needlessly high standards and complexity. Poor planning wastes the time of highly paid staff: overlapping safety briefings for example, or waiting for a berth to become available on a rig. Oil companies use bespoke parts, rather than standard ones, making it bothersome to get spares.

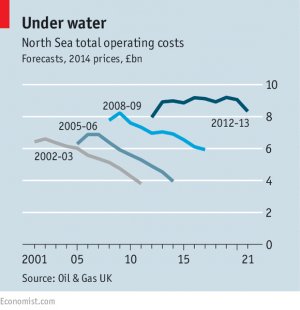

Reliability is “awful” says Dan Cole of McKinsey: offshore installations are working only 60% of the time, mainly because of ill-planned maintenance. Embarrassingly for the oil companies’ chiefs, their main industry body, Oil & Gas UK, has repeatedly predicted falling costs even as they have soared (see chart).

Even before last year’s sharp fall in the oil price, Britain’s North Sea operators were in trouble. With their oil fetching $100 a barrel, an eighth of their production was loss-making. McKinsey reckons that at $55 (a price it hit in March before recovering to $62 now), barely half is profitable.

The answer—pushed hard by the British government—is for the industry to copy the lean-production techniques that reshaped other industries, such as carmaking. Officials speak admiringly of Aera Energy in California, owned by ExxonMobil and Shell, which has turned onshore oil and gas extraction there from a Cinderella into a beauty queen. It treats well-drilling as a manufacturing process, managed by a single team from design to implementation.

A study for the Society of Petroleum Engineers highlights Aera’s use of just-in-time planning, careful mapping of work processes to cut waste, decentralised decision-making, standardisation, the use of visual tools to keep managers informed, and close collaboration with suppliers. Aera consciously models itself on Toyota, the Japanese carmaker which pioneered lean production. In 2011, Aera won an award for excellence in manufacturing—the first oil company to do so.

That approach will not transplant instantly offshore, where cost and complexity are inevitably greater. But smaller American oil-exploration firms with offshore operations, such as Apache and Murphy, have shown what focusing on efficiency can achieve.

That approach will not transplant instantly offshore, where cost and complexity are inevitably greater. But smaller American oil-exploration firms with offshore operations, such as Apache and Murphy, have shown what focusing on efficiency can achieve.

Even bigger oil companies do better elsewhere. Production in the Gulf of Mexico is more efficient than in the North Sea. The increased regulatory burden since the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2011 has not led to a big increase in costs. On one measure of reliability, Norway’s oil industry scores one-third better than Britain’s, according to McKinsey. One reason is less outsourcing (which reduces complexity); another is exceptionally high labour costs (which stimulate managers to look for efficiencies). The Norwegians’ spending on research and development is higher, too.

As big oil companies freeze capital spending and mull an accelerated withdrawal from the North Sea, a wave of restructuring and dealmaking is looming. In theory small, nimble low-cost companies could move in, using innovative techniques to extract the 24 billion barrels of oil (about 40 years’ production at current rates) still remaining on the continental shelf, though mainly in smaller deposits. But such firms need guarantees that they can access pipelines and terminals.

Britain is now urgently promoting a “thoughtful, collaborative approach” says Andrew McCallum of the government’s new Oil and Gas Authority. The aim is to cut costs, safeguard infrastructure, manage decommissioning sensibly and attract investment. It can impose binding “improvement notices” on errant firms. Tax breaks could be offered too. It may work: bargain-hunting private-equity firms are eyeing the offshore industry keenly. However, once seen as a British success story, the North Sea now looks anything but.

See also:RELATED VIDEO

Offshore wind power refers to the construction of wind farms in bodies of water to generate electricity from wind. Better wind speeds are available offshore compared to on land, so offshore wind power’s contribution in terms of electricity supplied is higher...

Offshore wind power refers to the construction of wind farms in bodies of water to generate electricity from wind. Better wind speeds are available offshore compared to on land, so offshore wind power’s contribution in terms of electricity supplied is higher...